Knead to Know: Unlock the Secrets of Sourdough

By Mitchel Lockwood

Published January 15, 2025

Certificates Mentioned in this Post: Professional Certificate in The Science of Cooking

With the Solstice now behind us, and daylight hours dwindled to a minimum, it seems like nature itself is reminding us to slow down. It's time to ready the nest and perfect your hygge; winter is here. And that means, it's the perfect time for sourdough.

It's true that September is dedicated to sourdough, and that makes sense. A bread that requires a little extra care and work to secure that coveted, warm crumb is the perfect symbol for the month that sees us rushing around to tie up the last ends of summer and prepare a cozy home. But sourdough rises beyond any one month, and it's not any less delicious on a cold January night. Maybe it's even better.

Beer. Kombucha. Kimchi. Tempe... Sourdough. If you've been on the internet for the last five years, there's no doubt you have heard about one of these fermented foods. It's the hot new ancient preservation method that's taken the internet by storm.

It seems each has had their moment in the sun (unless you're fermenting grapes to make wine, then limited ultraviolet light is key), but none like sourdough. After all, while there may be an Oktoberfest, only sourdough has the fermented honor of getting a whole month.

Before the spring comes with its flowers and new beginnings, I want a taste of what sourdough is all about. And I know just the place to look - Food Fermentation: The Science of Cooking with Microbes.

Magic Glop from an Ancient Past

You probably know that sourdough needs a starter, but where did it all start? As Eric Pallant, educator and author of Sourdough Culture A History of Bread Making from Ancient to Modern Bakers, explains in his lecture on the bread, starter was the original means of leavening bread.

"That was the receipe that we used since the dawn of civilization... you mix together flour and water and salt and some magic glop that you saved from the last time you baked and you make something and repeat it and you get bread."

It's a process that has been repeated since the dawn of the first civilizations in Mesopotamia. Archaeologists have even found evidence of sourdough starter's use as far back as 3700 BCE. Some suspect the history of the food extends potentially thousands of years before that.

From the stone age to the internet age, that "magic glop" still has a hold over us and special place in our fridge.

Sourdough's Moment

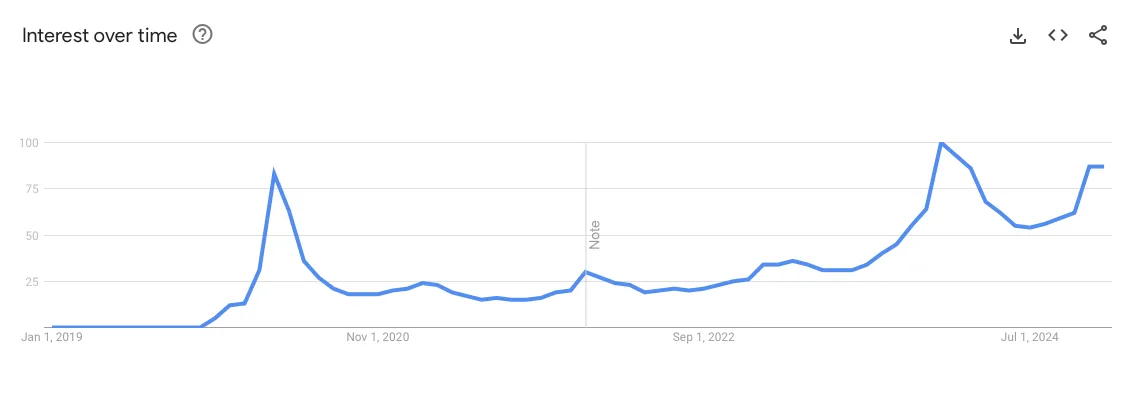

During the pandemic, no food had a moment quite like sourdough. Google Trends keeps the score on "sourdough bread" as a search term:

The first March, when we all learned what was in store for 2020. searches for "sourdough" increased over 500%. In our panic and grief-stricken state early on in our social isolation, many of us reached for the starter. There's something almost poetic about it. As we were all stuck fermenting in the house, we were inspired to make a bread prepared in much the same way.

There's certainly something scientific about it.

The Science of Sourdough

From the fermentation process to the maillard-browning reaction in the baking, it turns out there's a lot of science behind that "magic glop." When flour, water, salt, and microbes combine, flavor happens.

It all depends on the type of starter. In some ways the process is much the same. When these components are fermenting together, enzymes in the flour break starch down into smaller and more digestible units. That makes sugars bioavailable to yeasts and bacteria, which feeds on the sugars and reproduce. As they digest the sugars, the microbes generate carbon dioxide, acids, and alcohol (so that's where beer comes from).

But all bacteria are not equal. And different starters attract different types. These different types of bacteria can be split into two broad categories:

Heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria: Attracted primarily to rye-based starts. Produces acetic acid, giving bread a vinegary, sour, and fruity flavor.

Homofermentative lactic acid bacteria: Attracted to wheat flours and wholewheat flours, producing only lactic acid. In wheat flours, this creates softer, cereal flavors.

Wholewheats tend to form a malty, nutty taste.

There's another flavor causing reaction that happens when you bake the bread, making that delicious golden brown crust. That's known as the Maillard-browning reaction, which you can read more about here.

Do I need to knead?

That depends on how soon you will need it. The process of kneading helps to coax the gliadin and glutenin in a flour together to create gluten. That's because by itself, dry flour has no gluten - it must be created (Feel free to take this into your next trivia night).

That's important, because gluten forms the structure of the bread. It's the backbone that will support all of those delicious flavors primed in the fermentation process. Without gluten and its airy, yet structural quality, we would all be stuck eating bread bricks.

There are plenty of no knead recipes that stretch and fold dough before leaving it to develop. This is repeated, and in time the gluten structure forms just as it would if someone traded time for effort and kneaded it.

A Starter of Your Own

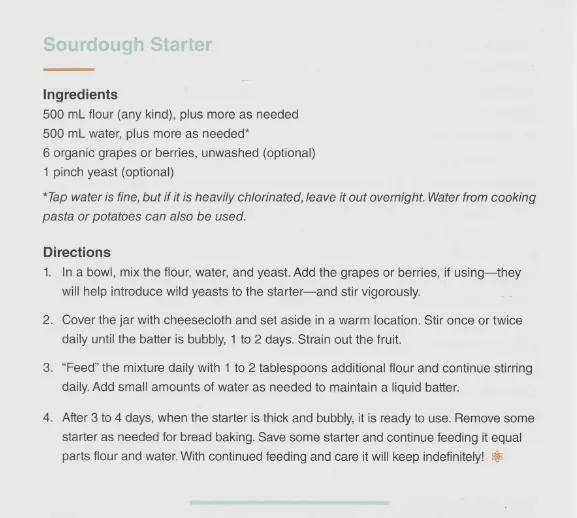

The Harvard faculty that helped make our course have the informational ingredients you need to help make your bread. The first thing you need is a starter.

Here's a recipe that comes from Science and Cooking: Physics Meets Food, from Homemade to Haute Cuisine by Michael Brenner, Pia Sörenson, and David Weitz.

Sour'do As You Please

The world is your oyster, but with winter now in full effect, your oyster may be much of your world for the next few months. Whether you knead it or don't knead it, or whether you pass over rye for some wheat flour, there are literally endless possibilities when it comes to making sourdough.

If that sounds exciting, or you're determined to become the resident expert on all things fermentation and sourdough amongst your friends and family, check out our course on fermentation or our other courses on the science of cooking:

Science & Cooking: From Haute Cuisine to Soft Matter Science (Chemistry)

Science & Cooking: From Haute Cuisine to Soft Matter Science (Physics)

Food Fermentation: The Science of Cooking with Microbes

Need more details on these or or other learning opportunities? Learn more here.

Related ArticlesBringing Science Into Your Holiday Cooking Top 10 Online Courses for Personal Development |